Lex Machina is proud to announce that our Legal Analytics platform is now extended to securities litigation. For the first time, practitioners in this area now have the ability to analyze legal data, helping them to win clients and cases. From showcasing experience with judges and districts in client pitches (or sizing up a law firm’s experience), to outcome data helpful for estimating risk, a data-driven approach provides a new universe of facts helpful to your cases and to your business.

This blog post focuses on a small subset of Lex Machina’s securities litigation data, the 932 securities cases terminating last year (in 2015). We will analyzes those cases in four parts, looking first at where the cases are filed and which judges hear them, next at which parties file the cases and which firms handle them, then at the findings and resolutions of those cases, and concluding with a short analysis of the damages awards from those cases.

While the conclusions drawn in this post have value from looking at the industry as a whole, Legal Analytic’s real power lies the ability to find the data that most closely fits your particular circumstance – something no static report can fully do. This post is meant to help practitioners understand some of the securities-related data available, and to inspire attorneys to consider how mixing and matching that data to their needs can make their practice more sophisticated (and less tedious).

I. Districts and Judges

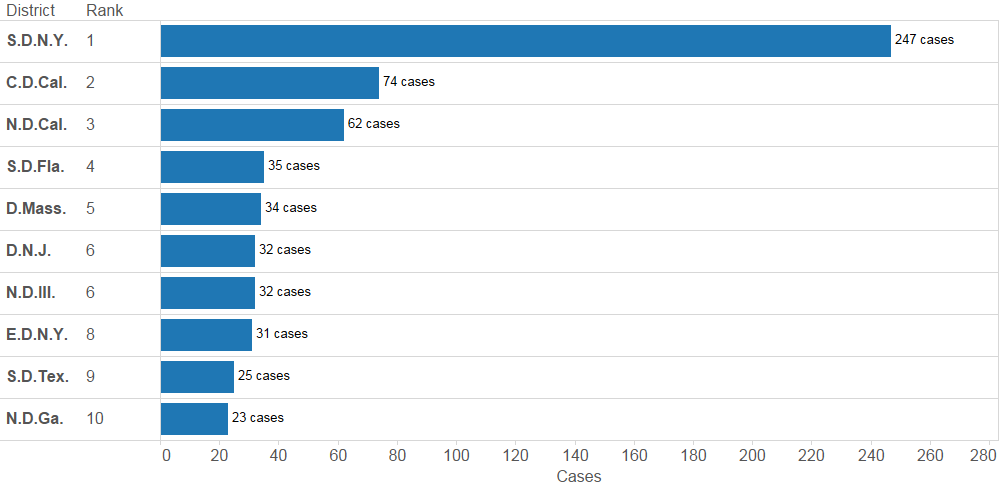

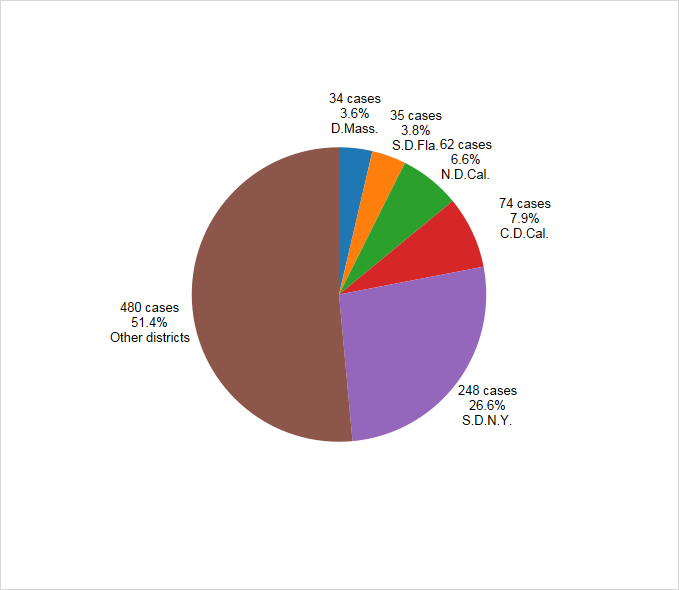

Securities litigation is heavily concentrated in the Southern District of New York (247 cases) (see Figs. 1-2). The next two top districts are the Central District of California (74 cases) and the Northern District of California (62 cases), each of which have had dramatically fewer cases terminate than S.D.N.Y.

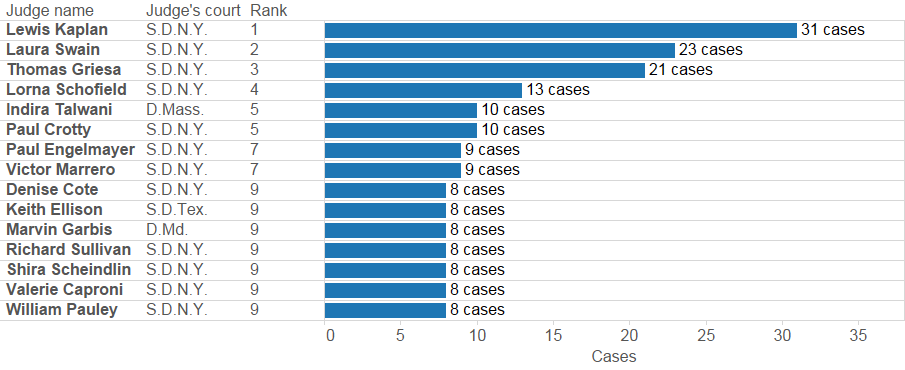

The top judges reflect S.D.N.Y.’s predominance – of the top 15 judges, all sit in S.D.N.Y. except for three – Indira Talwani (D.Mass., 10 cases), Keith Ellison (S.D.Tex., 8 cases) and Marvin Garbis (D.Md., 8 cases) (see Fig. 3). Judge Lewis Kaplan had the most cases terminating in 2015, (31 cases).

Fig 1: Top districts

Fig. 2. Top districts, percentage of whole

Fig. 3: Top judges

II. Parties and Firms

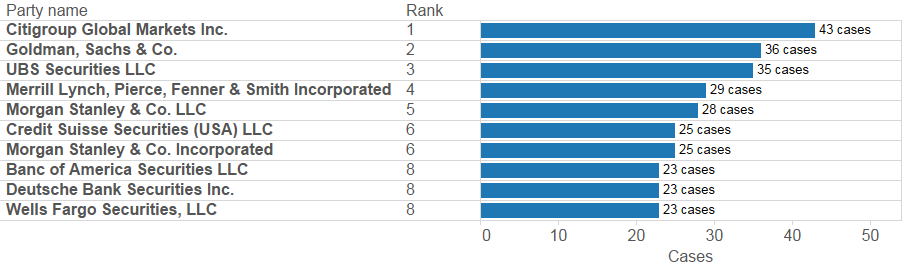

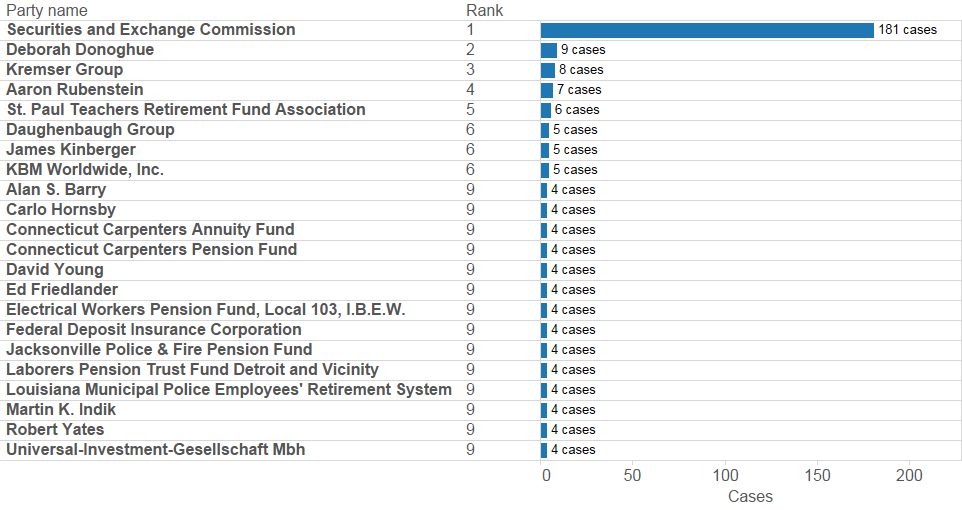

The top defendants are Citigroup Global Markets (43 cases), Goldman, Sachs & Co (36 cases) and UBS Securities (35 cases) (see Fig. 4). The SEC is the top plaintiff in securities litigation by a large margin, filing just under 20 percent of the cases terminating in 2015 (see Fig. 5). No other plaintiff had more than 10 cases. However, after the SEC, the list is quite varied, including both individual shareholders, retirement and pension funds, and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC).

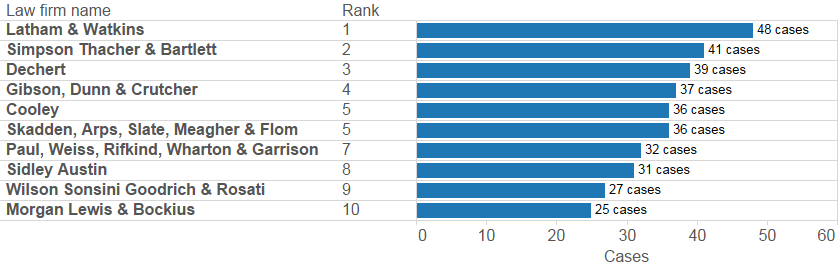

The top law firms representing defendants are Latham & Watkins (48 cases), Simpson Thatcher & Bartlett (41 cases) and Dechert (39 cases) (see Fig. 6).

For plaintiff side work, the top firms are Pomerantz (107 cases), Robbins Geller Rudman & Dowd (99 cases), Glancy Prongay & Murray (46 cases) and the Rosen Law firm (46 cases), aside from the SEC itself which represented itself with in-house attorneys in each case it filed (see Fig. 7).

Fig. 4: Top defendants

Fig. 5: Top plaintiffs

Fig. 6: Top defense firms

Fig. 7: Top plaintiff firms (excluding the SEC)

III. Findings and Resolutions

Lex Machina’s platform categorizes findings in securities litigation, according to the statutes and defenses invoked, recognizing three violations and three defenses.

- Securities Act Violation

- A violation of the Securities Act of 1933, e.g. § 11, § 12(a)2.

- Exchange Act Violation

- A violation of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, e.g. § 10(b) / SEC Rule 10b-5.

- Other Securities Violation

- A violation of any of the following federal securities laws: Trust Indenture Act of 1939, Investment Company Act of 1940, Investment Advisors Act of 1940, Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010, or Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act of 2012.

- Statute of Limitations Defense

- A defense against a securities claim that applies either when a time bar limits the duration that a defendant may be liable for a securities violation based on when the plaintiff discovered or should have discovered the securities law claim, or when an applicable statute of repose caps the limitation’s period of “litigation uncertainty.”

- Plaintiff Knowledge Defense

- A defense against a securities claim based on the fact that the plaintiff knew of falsity or omission in the securities registration.

- Cautionary Language / Safe Harbor Defense

- A defense against a securities claim based either on the “bespeaks caution” judicial doctrine or the statutory “safe harbor” introduced by the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 (PSLRA) in which meaningful risk disclosures sufficiently qualify forward-looking statements.

Examining the findings for the cases terminating in 2015 reveals some interesting facts: Securities Act violations and Exchange Act violations were the most frequent findings (95 cases, and 139 cases respectively) (see Fig. 8). No Securities Act violation was found rarely, in only 6 cases of those terminating in 2015. Of the defenses, the statute of limitations defense was the most frequently invoked (17 cases).

The majority of Securities Act violation findings are made on consent judgment (66 cases) or default judgment (34 cases) – few reach summary judgment (16 cases) or trial (5 cases), and the pattern for Exchange Act violations is similar (see Fig. 9). Statute of limitations defense has most frequently been raised at the judgment-on-the-pleadings phase, while safe harbor defenses are raised at summary judgment.

Securities cases most often are settled (214 cases by stipulated dismissal) or are won by the plaintiff, typically on default (35 cases) or consent judgment (107 cases) (see Fig. 10). Procedural outcomes are also common in securities litigation, particular consolidation and multidistrict litigation.

Fig. 8: Findings by type

Fig. 9: Judgment types by finding

Fig. 10: Case resolutions

IV. Damages

To make it easier to analyze the cases that matter most to practitioners, Lex Machina breaks down damages awards in securities litigation, recognizing four types of damages (in addition to cost and fees, excluded here):

- SEC Penalties

- Damages awarded for violating SEC regulations. This penalty may be an amount up to what the defendant made from the violation (e.g. the disgorgement amount) or may be based on a statutory amount for each violative act or omission.

- Disgorgement

- Damages awarded based on the legal theory that the defendant should not benefit through ill-gotten gains from the securities law violation. The damages amount is equal to the profits made due to the violation.

- Other Securities Damages

- Compensatory damages attributable to a securities law violation.

- Approved Class Action Settlement (Securities)

- A settlement amount approved by the court, involving the defendants and a “settlement class” certified at the time the settlement was approved or a certified class approved prior to settlement. The court is the protector of the putative class or certified class and must hold a preliminary fairness evaluation and a formal fairness hearing with notice to class members and government officials.

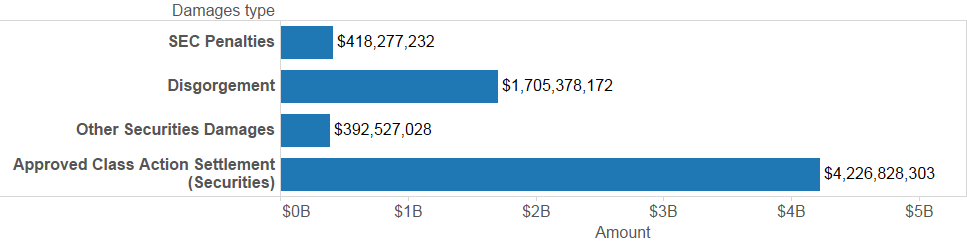

Approved class action settlements are by far the largest category of damages, with over $4.2 billion in damages awarded in cases terminating in 2015 alone. Disgorgement damages (corresponding to profits made from the violation) accounted for another $1.7 billion, while SEC penalties totaled only $418 million.

Fig. 11: Damages

All charts reflect data from the 932 securities cases terminating 1/1/2015 – 12/31/2015. Lex Machina’s securities coverage is broader, extending from cases pending 2009 through the present.