On Monday, May 22, 2017, the Supreme Court issued a slip opinion in the case TC Heartland LLC v. Kraft Foods Group LLC (Dkt. No. 16-341).

The court unanimously* held that, under 28 U.S.C. § 1400(b) (the statute governing venue in patent suits), a domestic corporation “resides” only in its state of incorporation, consistent with its ruling in an earlier case, Fourco Glass Co. v. Transmirra Products Corp., 353 U. S. 222 (1957). The Court rejected arguments that the general venue statute, 28 U.S.C. § 1391(c), which was amended post-Fourco and twice since § 1400, overrode the definition of residence in § 1400(b) with a more expansive one that made residence coextensive with personal jurisdiction. In doing so, the Court overruled the Federal Circuit’s decision in VE Holding Corp. v. Johnson Gas Appliance Co., 917 F. 2d 1574 (1990).

* Justice Gorsuch did not participate in the decision.

What Does That Mean and What Did TC Heartland Change?

Why is a seemingly technical matter of statutory interpretation so significant?

Before this decision, a plaintiff looking to sue a corporation for infringing its patent could choose any jurisdiction where the defendant did significant business. Large corporations doing business all over the country (or the world), especially over the internet, were therefore subject to suit in virtually any district court.

This arrangement was consistent with the general principles of tort jurisdiction. If you were injured by a kitchen appliance or consumer item, you could sue the responsible company in your home district rather than being forced to travel to the corporation’s home district.

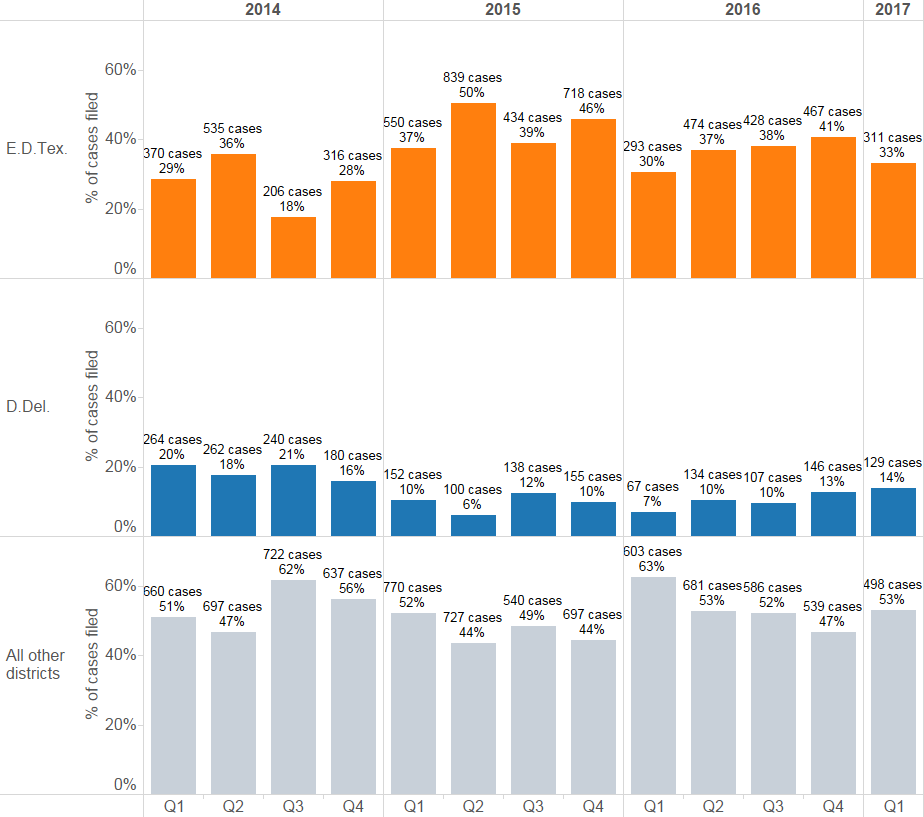

However, allowing plaintiffs this broad choice in the patent context has resulted in a disproportionate number of cases being filed in the Eastern District of Texas (E.D.Tex), as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Percentage of cases in the Eastern District of Texas, the District of Delaware, and all other districts combined, by quarter.

Between one third and one half of patent cases are now filed in a single district – the Eastern District of Texas. The next highest-ranked district, the District of Delaware (D.Del), only sees about 10% to 15% of the cases filed, and the drop-off is even more significant after that.

The effect of the TC Heartland decision will almost certainly be to reduce the proportion of cases filed in the Eastern District of Texas, because the holding restricts plaintiffs’ choice of venue to the district where the defendant is incorporated or has a “regular and established place of business.” It also very likely that a greater proportion of cases will be filed in the District of Delaware, as it is a popular place for large companies to incorporate.

Although the Court’s opinion rests on reconciling specific language between the two statues and with the earlier Fourco decision, many amicus briefs and commentators were focused instead on the policy considerations and practical effects.

In evaluating whether limiting the broad venue options of patent plaintiffs is a good idea, it is instructive to consider how a patent plaintiff is unlike the hypothetical plaintiff injured by the defective kitchen appliance or consumer product. The most salient distinction is that, in patent litigation, there exist high-volume plaintiffs.

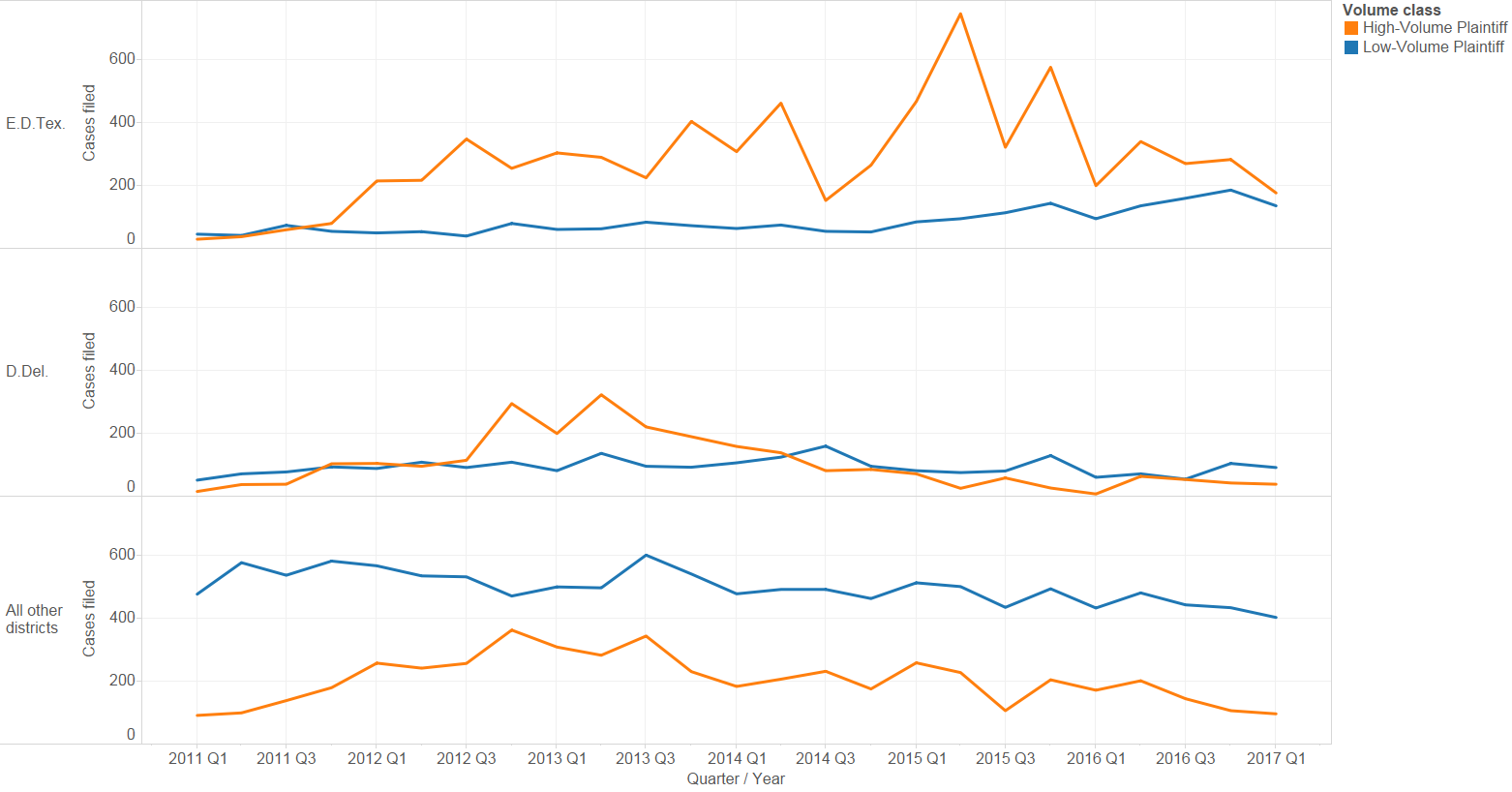

High-volume plaintiffs (HVPs) are those that have filed 10 or more patent cases within a 365-day span. Lex Machina developed this classification as an alternative to “non practicing entity” (NPE) or “patent assertion entity” (PAE) analysis, terms whose exact meaning is often ambiguous. Unlike other measures, high-volume plaintiff status is an objective and behavior-based measure that is not susceptible to bias in application.

As shown in Figure 2 below, HVPs almost exclusively drive the popularity of the Eastern District of Texas. They are also primarily responsible for filing spikes, including those previously covered on this blog as a result of procedural developments real and rumored. These trends suggest that HVPs are generally sophisticated, repeat players who strategically file of many of cases in districts where (and when) even a small advantage is perceived.

TC Heartland will significantly restrict the HVPs’ choice of where to file their cases, and in doing so it recognizes how the patent litigation often differs from the the stereotypical power imbalance (small plaintiff vs. large corporate defendant) that exists in the general tort context. While the restriction also applies to other, low-volume plaintiffs, it is less likely to be a concern for them; those cases are more likely to involve operational companies on both sides and less power imbalance. Given the sensitivity of the HVPs to potential changes in the law (and the corresponding volatility of their case filings), it stands to reason that this decision will depress HVP case filing numbers, although by how much is unclear as of yet.

Figure 2: High-volume plaintiff activity (orange) vs other patent litigation (blue)

What To Expect Next?

In the new environment of uncertainty created by this sea change in patent venue rules, both companies and law firms can benefit even more from having hard data.

Those facing the prospect of litigation in the District of Delaware should want to know: Are the odds of winning better? Do cases get decided more quickly? Which counsel have the best track record there? Which companies are likely to soon need representation there, and how can they best be pitched?

The decision may also cause plaintiffs to explore other new jurisdictions that currently don’t see as much patent litigation. For litigants and lawyers before unfamiliar judges, knowing the data landscape can provide an advantage.

Lex Machina subscribers can get started right away exploring the answers to these questions on our site in realtime, and others can request our recent Patent Litigation Year in Review report, which provides insight into these and many more trends.